In 1940, shortly after the outbreak of WWII in North Africa, the British postal system faced a daunting problem. The volume of letters being sent to and from British soldiers back home was impossibly large. With aviation still in its infancy, the letters weighed too much for them to be carried by plane. Instead, they were routed around the southern tip of Africa, taking up to 6 months to reach their destination. Luckily, a new technology was there to save the day: “Airgraph”.

Airgraph was developed by Recordak, an English subsidiary of Eastman Kodak. The Airgraph process was simple. Soldiers and their families wrote their letters on special forms. The forms were fed through a machine that photographed them onto microfilm that was 50x lighter than paper. And the film was flown to its destination and printed out through another Airgraph machine.

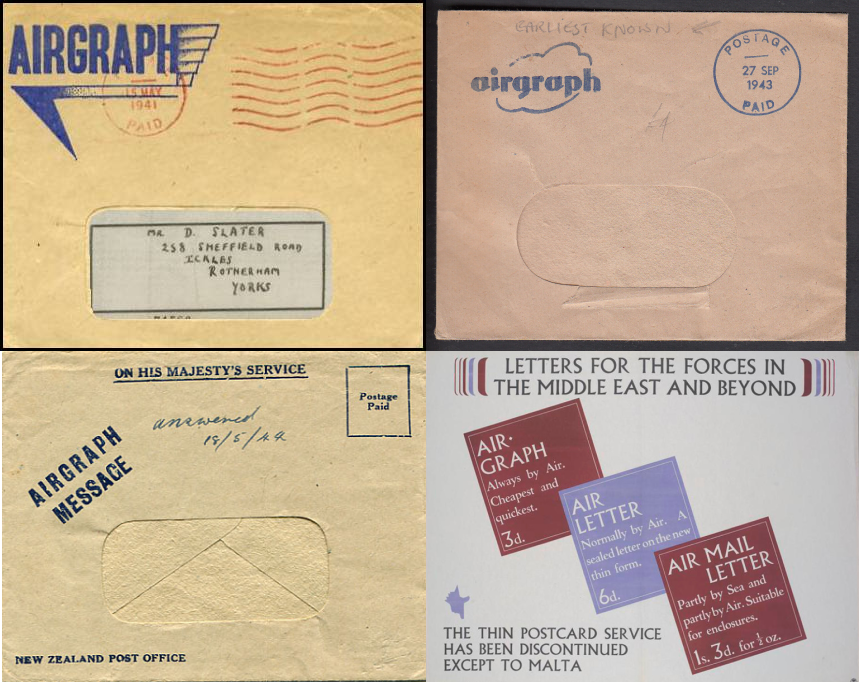

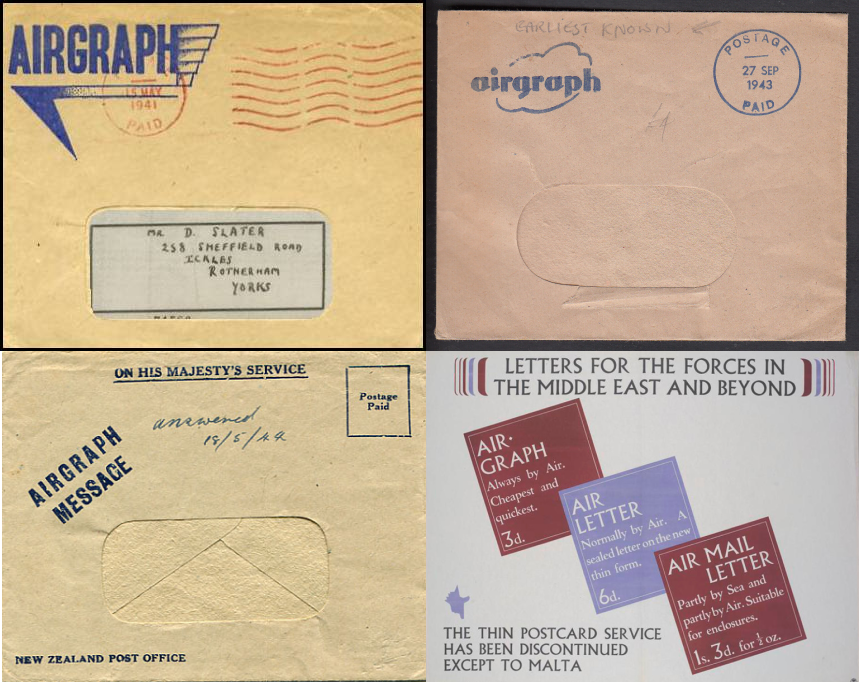

Real airgraph envelopes & an ad for sending option

Airgraph was an immediate success, shortening the six month journey to two weeks. Airgraph was a physical compression algorithm — 1,600 letters written on paper weighed 50 lbs, now they weighed 5 ounces. “I received an Airgraph” became a common saying. By the time families in London started returning messages, roughly 1,000,000 Airgraphs had been sent1.

Today, a new Airgraph is needed.

The problem is that all of our information is fragmented into silos — email, docs, Slack, etc. This makes it hard to communicate and much harder to find and use information than it should be. It’s resulted in an overload of information that’s impossible to manage. This is exacerbated by the fact that we live in a world where communication means tens, hundreds, or thousands of people on your team located across different spaces and time zones.

So, just like the original Airgraph, we must compress information to solve the problem.

That’s why we’re building AirGraph, a service that integrates all of your fragmented information: email, messaging, documents, notes, tasks, and calendar. It’s the easiest way to communicate.

Make no mistake, Microsoft rules the world. The average twitter-addicted urbanite information worker might believe the whole world runs on Google Workspace (GSuite), Notion, and Slack, but they would be wrong. Microsoft Office’s annual revenue is $45 billion2, with about $39 billion coming from business to business sales. Slack’s is ~$1 billion. And while Google doesn’t break out Workspace’s revenue, at > 6 million users, most analysts assume it’s likely a billion dollar business. Microsoft is the 20x gorilla of work information and communication software.

That being said, it would be a fool’s errand for any startup to target Microsoft out of the gate. Not because they can’t make better software, but rather because they can’t compete on distribution. Therefore, to tackle this problem, the world we must focus on is the smaller yet mighty pool of information workers that are Gmail and Slack (G-Slack) users.

The G-Slack market is one that does value the smaller details of product craftsmanship. Slack is a beautifully designed product, and Google Docs is by and large hilariously better than Microsoft Word. While Slack learned the hard way3 distribution is still king, they still have ~20 million people using it daily — and for good measure. Slack solved two distinct problems: frictionless instant 1:1 communication and team-wide collaboration and transparency. They did this with DMs and Channels respectively.

While Slack excels at those two things, the whole is less than the sum of its parts. Why? Because Slack atomized the wrong unit of information and siloed it. Let us explain…

Writing, whether a long document or short message, provides a natural buffer between what one is thinking and what one says — that buffer is time. In that time ideas become plans, and plans become reality.

When Slack atomized the direct message, they killed the buffer of time. Everything became instant. By removing the buffer, Slack killed the process of turning disparate information into coherent business logic and replaced it with an illusion of accomplishment. Time was traded for expediency at the expense of clarity.

Napoleon famously waited three weeks to open his mail, as he found any truly urgent matters would find their way to him — and the majority of the mail would have resolved itself by the time he opened it. Slack is Napoleonic in reverse. What was once a high signal memo became a dripping faucet of noise left for both the reader and writer to parse.

In Slack’s defense, the evolution of written communication is the story of expediency. A letter by horseback turned into a telegram, which turned into an interoffice memo, which turned into a fax, which turned into an email, which turned into a slack.

The average worker has email, Slack, documents, notes, tasks, calendar, and at least 2-3 bespoke apps for their job. Even without Slack, that’s a lot. Add in constant direct messaging, it becomes too much.

Slack Channels offer team-wide collaboration and transparency. For teams < 20 people, channels are awesome. It’s a better way to keep up with and add value to a conversation centered on a specific topic, opposed to email or a plethora of Google Doc comments. For teams > 20 people, channels become a distraction — distractions themselves and the sheer volume of them.

Problem being, it’s not that Slack Channels aren’t transparent, it’s that they are silos of direct messages and nothing else. Their tagline was “where work happens” and their mission was to create an Operating System for work. The Searchable Log of All Communication and Knowledge (Slack) somehow missed the operative word: All.

That’s where AirGraph comes in.

AirGraph is predicated on the notion that there is no difference between a message and document. A document is simply a message that persists over time. We believe integrating core workflows breaks down silos and makes life a lot easier, but as we’ve seen, it’s the atomic unit that does the heavy lifting. Just as the British soldiers in WWII sent and received “airgraphs”, we’ve created a new atomic called an ‘airgraph’.

The best analogy to the new airgraph atomic unit is the memo. Memos, short for memorandum — meaning “that which is to be remembered”, have gone out of style4.

Memos blur the line between message and document. They can be a short message addressed to a few people, or a 40 page plan architecting some great human endeavor. In fact they are still the tool used by the US Government to make decisions. They also acted as what we now know as “posts”. Point being, they were a customizable format that allowed for both effective communication and the documentation of important information.

Once again, we traded expediency at the expense of clarity. We replaced memos with long documents wrapped in messages and emails. The problem is that these two primitives can’t see each other. No matter what you do with today’s current tooling, whether it’s G-Slack, Microsoft, or the hottest “productivity app”5, the context gets stuck.

Memos weren’t wrapped in messages, they were messages! When people replied to memos, the conversation was appended to the original memo forming a chain of high signal information. Resulting in context.

An airgraph can be thought of as an interactive memo. A memo with the ability to @ someone in-line. A memo with the ability to link to any other type of information such as an email, message, task, event, note, or, of course — another memo. A memo that can be replied to. A memo that can be broken apart and snapped back together. A memo with a clear history. A memo with multiple editors. A memo that is real-time. A memo that can receive replies. A memo that can be forked, starred, or watched. A memo that compresses information as to be of the highest signal. A memo that never loses context.

Currently, you cannot add an email to a document. You cannot turn a message into a task. You cannot add a document inline inside of a message. You can’t assign tasks from the meeting notes you took inside an event. Your information cannot talk to each other, in fact, it cannot even see each other. AirGraph shatters this paradigm, makes the aforementioned actions trivial, and enables infinite possibilities.

Microsoft runs the world. They will get stronger by adding ChatGPT into every Office product. G-Slack has market power in the most dynamic segment. Notion is coming online. But they’re all siloed. And they’re all based on the wrong atomic units of information. All with a cost of context and utility.

This new atomic unit, combined with the integration of all types of information, results in a world where information is open and communication is easy.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy in business is when an employee makes the wrong decision due to missing readily available information that would have provided the context needed to make the right decision. Never again.

Communication is the basis of all human progress. Advances in communication technologies took us from the stone age to the information age. The phonetic alphabet, writing, the printing press, the telegraph, and every ensuing innovation led to a step function increase in longevity and prosperity.

The opportunity for AirGraph is to build both the central nervous system6 for you and your business and to build a world where communication becomes frictionless.

To illustrate the scope of the opportunity, it’s not just startups and pure information companies that will benefit. Massive companies who only deal in the world of atoms — Caterpillar, Ford7, or Levi’s — are no more or less the information generated by their employees. And their efficacy is a direct result of their ability to communicate important information seamlessly with colleagues, customers, investors, and suppliers.

Communication is essential, and we believe this second iteration of AirGraph will materially improve the odds of success for anyone that uses it.

We accept path dependence but reject historicism.

While those British soldiers were halfway around the world communicating by Airgraph, Winston Churchill famously remarked, “When great forces are on the move in the world, we learn we’re spirits — not animals.” The post-covid world is still in the midst of a great reshuffling, whereby hybrid work has become the de facto standard. The current communications architecture is built for a soon-to-be distant past. Great forces are on the move again. Join Us.

ChatGPT’s take: Memos have declined in popularity due to the proliferation of more efficient and effective methods of communication, such as email and messaging apps. These methods allow for quicker and more convenient communication, as well as the ability to easily share documents and other media. Additionally, the widespread use of these technologies has made it easier for people to work remotely, which has further reduced the need for traditional memos as a means of communication within an organization. ↩

New does not always mean better, especially when quality is replaced with expediency. The Egyptians were able to build the Pyramids without using email or the latest project management software. We built the Hoover Dam, cured Polio, split the atom, and went to the Moon without email too. ↩

https://kwokchain.com/2019/08/16/the-arc-of-collaboration/ ↩

How does Ford make a car? First, they get money to build the cars. They can only do this if they communicate effectively with investors, lenders, and buyers. Then they order the machines and parts, hire the workers, and secure a place to build them. This is an incredibly complex process with many moving parts (pun intended). In order to do this, they will generate a ton of information that needs to be communicated effectively across different departments and stakeholders. If they fail to order the parts at the same time the workers are to begin building, the whole operation will break down and delays will ripple down through the rest of the steps such as assembly, marketing, and distribution. Eventually, the independent dealership 2,000 miles away has to turn customers away, and would-be-Ford-buyers drive home in a new Chevy. ↩

First published on January 12, 2023